Over-Engineering as a Coping Mechanism

In which I build an entire web app to avoid thinking for thirty seconds.

I needed to decide the order of three speakers at an event.

Three people. All great. Any of them could go first, second, or third. There’s the usual caveat: the person who goes last is sometimes seen as the most important, but they also risk getting their time squeezed if earlier speakers run long. (Which, incidentally, is exactly what happened.)

These were people of equal seniority in this context. A simple decision. The kind of thing a normal person would resolve in thirty seconds.

But I’m neurospicy, and one of the things I’ve learned about my brain is that low-stakes decisions with no clear “right answer” are exactly where I get stuck. I’ll ruminate. I’ll weigh factors that don’t matter. I’ll think about it again tomorrow.

I didn’t want to do that. I wanted something slightly better than a coin toss—without having to think about how many coin tosses it takes to fairly order three items. (It’s more than you’d think, and now I’m already down a rabbit hole.)

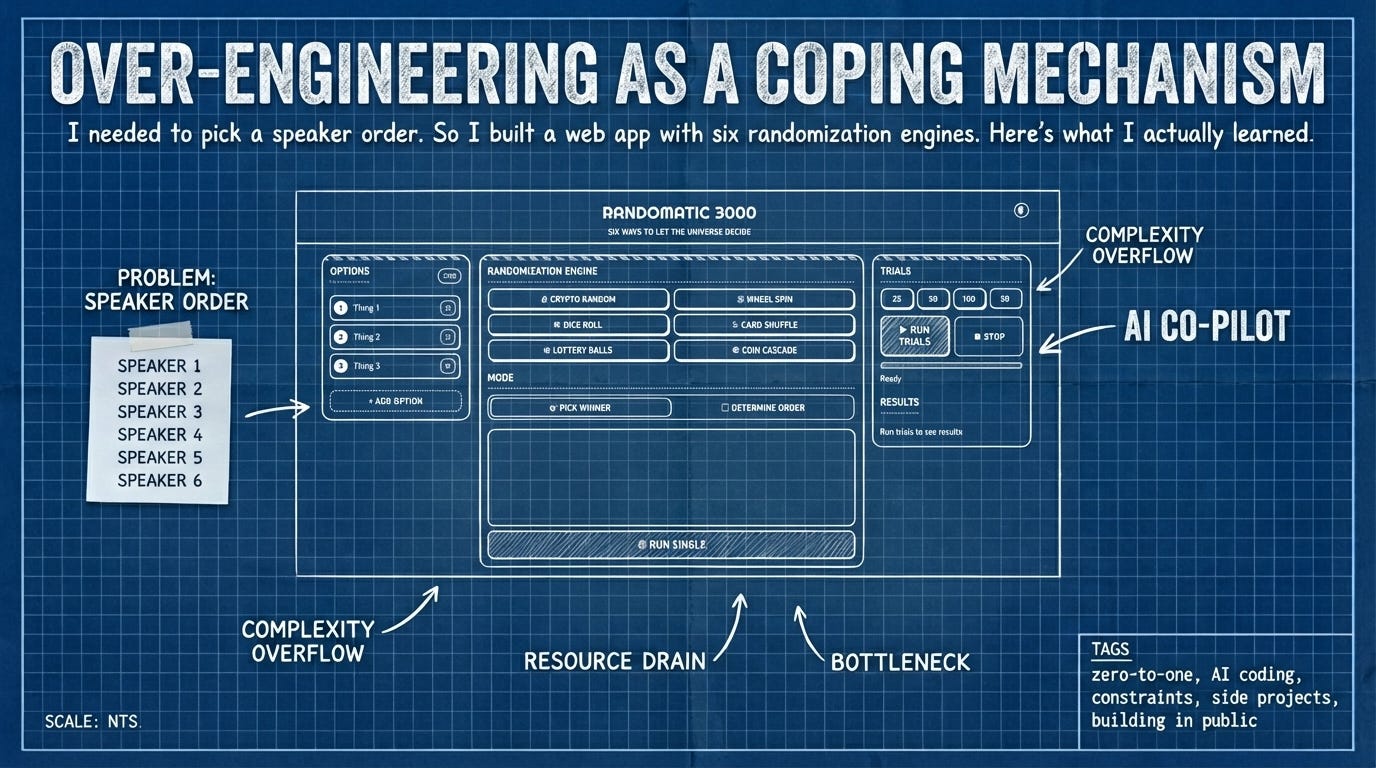

So I did what any reasonable person would do: I built a web app with six different randomization visualization engines.

Meet RandoMatic 3000.

The point isn’t the tool

Here’s the thing: I didn’t even use RandoMatic 3000 to make the speaker decision. By the time the tool was done, I’d already figured it out the old-fashioned way.

But now the tool exists. It’s live. It works. Other people have used it. And I practiced an entire zero-to-one workflow that I’ll use again on projects that actually matter.

This is the part that’s hard to explain to people who think building is about outcomes: sometimes the tool isn’t the point. The process is the point. The having-a-thing-that-exists is the point. The muscle memory of shipping is the point.

RandoMatic 3000 is aggressively over-engineered for what it does. Six visualization engines? Statistical trial mode? Dark/light mode toggle? For picking names out of a hat?

Yes. Because it was fun. Because constraints make projects interesting. And because I wanted to see if I could go from “vague idea” to “live on the internet” in a single working session using AI as my coding partner.

I could. Here’s how.

Start with the end, not the code

Before I wrote a single line of code—before I even opened a terminal—I spent time thinking through three things:

1. Desired outcomes. What does “done” look like? In this case: a working web app that randomly orders or selects from a list of items, with some visual flair, accessible to anyone with the link.

2. User stories. How will someone actually use this? They’ll land on a page, enter some items, pick a visualization style, and get a result. No accounts, no setup, no friction.

3. Constraints. This is the most important part, and the one most people skip.

Constraints aren’t limitations—they’re decisions made in advance that prevent scope creep and make the project actually shippable. Here’s what I decided:

Single-page web app. No multi-page routing.

No backend. Everything runs in the browser.

No login system. Anyone with the link can use it.

Single GitHub repository, deployed to Netlify.

HTML, CSS, JavaScript. React for the UI.

Test-driven development from the start.

Each constraint closed a door. And every closed door made the project smaller, clearer, and more likely to actually get finished.

This isn’t a software-specific insight. It applies to anything you’re trying to get from zero to one: the clearer you are about what you’re not doing, the easier it is to do the thing you aredoing.

Talk before you type

Once I had the constraints and outcomes clear in my head, I did something that might seem old-fashioned: I talked it out.

I use an app called MacWhisper—it runs OpenAI’s Whisper model locally and transcribes speech to text. I opened it, hit record, and just... talked through everything. The goals, the constraints, the user stories, the things I wasn’t sure about.

A few minutes of rambling became a text file. That text file became the context I fed to my AI coding tool.

This is one of the most important things I’ve learned about working with AI: the quality of the context determines the quality of the output. If you give an AI coding agent a vague prompt, you’ll get vague code. If you give it a detailed, thoughtful description of what you’re building and why, you’ll get something much closer to what you actually want.

Dictation is my way of getting the messy thinking out of my head and into a format the AI can use. It’s faster than typing, and it captures nuance I’d otherwise edit out.

The technical bit (feel free to skip)

If you’re not interested in the specifics of AI-assisted coding workflows, jump to the next section. The principles above and below are the transferable parts.

My AI coding setup for this project:

Tool: Factory Droid (though Claude Code works similarly). I like Factory Droid because it gives me access to multiple models under one account—Claude Opus 4.5 for heavy lifting, Gemini Pro for UI polish, OpenAI Codex for quick fixes—and their context management is excellent. Long sessions don’t require constant re-prompting after context compression.

Process:

Created a new directory, opened my terminal, launched the AI agent.

Pasted in my entire pre-specification dictation—goals, outcomes, constraints, user stories, everything.

Switched to Spec/Plan mode(Shift+Tab in Factory Droid, “Plan Mode” in Claude Code). This is crucial. In this mode, the AI researches and plans but doesn’t write code yet. You collaborate on the specification together.

Went back and forth several times on the spec. Each time the AI proposed a plan, I’d tweak it—clarifying epics, adjusting scope, adding constraints I’d forgotten. The goal is painful clarity before any code gets written.

Once the spec was solid, I approved it and let the AI start coding.

Why this matters: The spec phase is where most of the real work happens. I’d estimate a third of the total effort was pre-spec thinking, a third was spec refinement, and only the final third was actual coding and testing. Most people invert this ratio—they jump straight to code and wonder why projects get messy.

On testing: I always use test-driven development, even for small projects. Here’s why: I don’t read every line of code the AI writes, but I do read every line of the tests. If the tests are well-written and they pass, I have high confidence the code is solid. Tests are my verification layer.

On documentation: I keep an AGENTS.md file updated throughout the project. This makes it easy to switch models mid-session or pick up where I left off later. Good documentation is context you don’t have to re-explain.

The real work is testing

Here’s something that surprised me when I started working with AI coding tools: the coding part is actually kind of boring to watch. Files get created. Tests run. Servers spin up. It’s impressive the first few times, then it’s just... waiting.

The real work—the part that requires human judgment—is testing.

You have to test manually, as early as possible, as often as possible. You’ll find things that are completely broken, things that are subtly wrong, and things that technically work but feel off when you use them.

This is normal. This is how software gets built. The bugs aren’t failures; they’re the work revealing itself.

With RandoMatic 3000, the first bugs I found were UI issues. Elements in weird places. Layouts that didn’t make sense. I made a wireframe—and by “wireframe” I mean I drew a crude sketch on paper and took a photo—and showed it to the AI. Changes were made. Some tests broke. We fixed them.

Then I moved to end-to-end testing. I went to ChatGPT and asked for 15 different scenarios: “ways to pick the order for speakers at an event.” I dictated the context, got back a list of test cases—some good, some silly—and worked through them. Names that looked like code. Names in different languages. Edge cases that might break things.

Each round of testing surfaced more bugs. Each bug got fixed. This is the loop.

The great thing about AI as a coding partner: it doesn’t get tired, doesn’t get defensive, and doesn’t complain when you send something back for the fifth time. You can be as demanding as you need to be.

Ship before it’s perfect

When I felt reasonably good about the state of things, I pushed the code to GitHub and connected the repo to Netlify. A few minutes later, I had a live URL I could share.

I found more bugs immediately. Fixed them. Pushed again.

This is the part that trips people up: you have to ship before it’s perfect, because “perfect” is a state you discover through contact with reality, not through more planning.

RandoMatic 3000 isn’t perfect now. There are probably edge cases I haven’t thought of. Features I could add. Polish I could apply.

But it’s done enough. It exists. It works. People can use it.

That’s the bar for zero-to-one work: not “is it flawless?” but “does it exist and do the thing?”

What I actually learned

The tool was way more than I needed for a three-person speaker order decision. But building it taught me (or re-taught me) a few things:

Constraints are gifts. Every door you close in advance is a decision you don’t have to make later. “No backend” and “no login” turned a potentially sprawling project into something I could finish in a day.

The spec is the work. Two-thirds of the effort happened before any code was written. If you’re struggling to finish projects, you might be under-investing in the planning phase.

AI is a partner, not a replacement. I read every test. I made the wireframe. I did the manual testing. I made all the judgment calls. The AI wrote code; I made decisions.

Testing is where building actually happens. The first version is never right. The iteration loop—test, find bugs, fix, repeat—is the real process.

Sometimes the tool isn’t the point.I didn’t use RandoMatic 3000 for the original decision. But I have the tool now, I practiced the workflow, and I have something to share. That’s three wins from one silly project.

The links

RandoMatic 3000 — try it yourself

GitHub repo — see how the sausage was made

One question for you

I’m curious what this sparks.

Maybe it’s a project you’ve been circling but haven’t started. Maybe it’s a dumb tool you’ve thought about building but couldn’t justify. Maybe it’s just the recognition that sometimes the thing you make isn’t the point—the making is.

What’s something you’ve been tempted to over-engineer? Or: what’s a small, silly thing you could build that would teach you something bigger?

Hit reply. I read everything.

adam